Dental Insurance: A Time for Disruption

Health insurance is America’s greatest unmet need. Patients and providers suffer from price opacity, excessive claim denials, untimely patient care and lack of relational trust. When health insurance was created, it was intended to function as an employer-based program for the prepayment of hospital care1; however, a side effect of adding this bureaucratic layer is that, often, insurance complicates the clinical workflow, strains the provider/patient relationship and blocks appropriate reimbursement for the provider. Changes in medical insurance can alter dental insurance by shaping patients’ assumptions of how dental insurance can be applied to visits and procedures, influencing operations within dental insurance companies, and affecting regulatory/governmental changes that directly impact dental practices. Therefore, a basic understanding of medical insurance and its trajectory can empower the dental community to maintain and strive for a reimbursement system that is equitable and patient-centric. Innovation in technology — such as artificial intelligence (AI), automations, financial technology and alternative insurance models — have provided insight into the next frontier of the insurance industry and how it may impact dentistry.

Humble Beginnings of U.S. Commercial Health Insurance

The history of health insurance offers insight into how its role has evolved into a major player in regulatory and care management. The Great Depression set the stage for health insurance. Reduced healthcare utilization in hospitals coupled with a limited money supply gave rise and support for the Blue Cross plan. The American Hospital Association supported scaling of the Blue Cross program to allow these nonprofits exclusive rights to offer services through participating hospitals within a particular geographical area. Since exclusivity in a geographical area was a key tenant of these programs, hospitals were not in competition. Additionally, the nonprofit status was justified since the plans were intended to foster public welfare. At the end of the decade, 25 states enacted legislation to regard these hospital plans as health insurance and require that the nonprofits abide by existing insurance laws.2

The rapid expansion of health insurance occurred in the 1940s–1950s. During this time, World War II created a large population influx into the jobs market, which required companies to compete for workers. Providing benefits packages, including health insurance, allowed companies to be more competitive — to the extent that unions began using health insurance as a subject for bargaining. Additionally, companies could offer health insurance as a nontaxable wage, allowing companies to save heavily on wage-related federal taxes. As time progressed, multiple models of healthcare insurance arose, and the regulatory complexity continued to increase.

Decoupling Health Insurance: Medical vs. Dental Insurance

The crux of health insurance is uncertainty. Healthcare insurance companies calculate the risk of this financial uncertainty while still earning a profit.3 Everyone is exposed to at least some material risks. These risks can be mitigated by multiple means, one of which is insurance. Each subset of insurance (health, property, liability, etc.) cannot be weighed equally, since different categories of risk are not equivalent. In general, the severity and probability of a negative event occurring provides the framework for the level of risk.

The traditional health insurance benefit package provided by employers typically includes medical, vision and dental insurance. The likelihood of a catastrophic event resulting in financial bankruptcy is much higher within the medical category compared to vision or dental. In fact, medical debt accounts for at least 46% of all bankruptcies in the United States.4 For instance, a stroke can lead to a single high-value bill, or a diagnosis of a chronic condition, such as AIDS, can be costly over the long term. In contrast, the financial risk of dental treatment is much less compared to a catastrophic event. The financial protections that dental insurance offers for higher-value treatment (i.e., implants) is low. Additionally, the protection of dental harm is not balanced by the payment of the insurers.5 Therefore, dental insurance is unlikely to provide patients with an optimal value, particularly for the population with the ability to pay for basic dental services. According to 2014–2017 data, only half of nonelderly adults (ages 18–64) in the United States who had medical coverage also had dental coverage.6

Dental Insurance Is Affected by Medical Insurance Changes

Despite medical and dental insurance being fundamentally different, the two are inherently linked due to patient perceptions of insurance, single insurance companies offering both medical and dental, and insurance coverages and regulations set by the government. Dental patients are often confused about their insurance,7 and patients in general have limited knowledge about coverage details, costs and procedures as they relate to insurance.8 Dental and medical insurance are complicated. Frequent policy changes, regulatory complexity and insurance-specific jargon are also difficult for healthcare providers to navigate. In turn, the previous mandate by the U.S. government within the Affordable Care Act for its citizens to enroll in medical insurance or face a tax penalty could have been misconstrued as applying to dental coverage.

Trends in the public domain create pressure to reorganize or add regulations to health insurance that could lead to consequences in dentistry. For instance, the Affordable Care Act expanded medical insurance coverage, yet did not explicitly include dental coverage. Through Medicaid expansion, however, dental insurance coverage increased for children.9

In addition, the oral-systemic link has been extensively reviewed in several siloed fields — particularly the periodontal and cardiovascular fields. As further research strengthens the connection between oral health and overall health, the topic of dental insurance has been revisited by organizational and governmental stakeholders. There are data to show that having dental insurance increases the likelihood of visiting a dentist and improves a patient’s overall health status. More specifically, there is evidence to suggest that improvement in periodontal health can reduce the incidence of heart disease and preterm birth10 — both of which contribute to increased healthcare spending.

Trends in Medical and Dental Insurance

The largest source of health insurance coverage is from employer-sponsored programs. However, in the last 15 years, there has been a steady decline in employer-sponsored coverage.11 This trend is potentially due to lower participation rates in the labor market, the part-time “gig” economy and fewer companies opting to offer these benefits. While there are a multitude of reasons patients do not seek dental treatment, lack of employer-sponsored coverage is a large contributor.

Regulatory changes have affected the health insurance markets. In an effort to curb rising healthcare costs, healthcare providers were urged by an executive order to disclose their insurance-negotiated rates starting in 2019. To date, studies have shown that disclosure of pricing has not had any effect on healthcare spending, although it might have small effects on homogenous services that exhibit high degrees of price variation, leading to patient savings.12 In dentistry, a larger dental service organization/multioffice model is able to negotiate higher reimbursement rates from insurance companies. These increased rates might not affect patient balances; however, there is a general trend for patients and regulatory agencies to seek price transparency measures.

Transparency in health insurance payment to providers has been lacking. For instance, over 100,000 medical insurance policy changes occurred between March 2020 and March 2022 after the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to uncertainties for reimbursement requirements.13 Similarly, claim denials occur in approximately 12% of claims billed to medical insurance carriers — totaling $262 billion of denied claims annually (see Fig. 1).14 While there are multiple reasons for claim denials (registration errors, unclear medical necessity, incomplete documentation, incorrect coding, missing data, etc.), the rates of claim denials are increasing. The Office of the Inspector General (the governmental agency providing oversight to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) recently found a large discrepancy of claim denials between traditional Medicare, which has low claim denial rates, and commercial Medicare Advantage organizations, which were found to have sometimes delayed or denied care despite claims meeting rule requirements.15 Many of the same commercial carriers in the medical arena also offer dental insurance and, therefore, use similar tactics in the dental field. Although claim denials in dental insurance are less widely published, one study that analyzed the claims data from a large dental insurance company found that an average of 8% of claims were denied from total procedures billed.16

.png?sfvrsn=50140fc5_0)

.png?sfvrsn=50140fc5_0)

When compared with other high-income countries, the U.S. healthcare system ranks last in health outcomes, equity, access to care and administrative efficiency, despite spending the highest percentage of gross domestic product on services and procedures.17 Improved health outcomes being unrelated to the amount of healthcare dollars spent is not a new problem. Reimagining the U.S. healthcare system is complicated with no perfect options. Alternative models to health insurance are increasingly being implemented. Healthcare systems are starting to adopt value-based care (VBC) models, which intend to improve healthcare quality while also reducing costs (see Fig. 2). In some VBC models, a fixed cost is paid directly to the provider per patient to optimize their health, and additional bonuses are disbursed for maintaining positive quality metric and patient satisfaction scores. VBC models are being implemented with increased frequency in medicine, particularly for conditions with high costs to the healthcare system (i.e., diabetes, cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease). These systems have also been implemented in dentistry for multidisciplinary care settings, early childhood caries and oral surgeries.18

.png?sfvrsn=752edba_0&MaxWidth=1000&MaxHeight=600&ScaleUp=false&Quality=High&Method=ResizeFitToAreaArguments&Signature=0F6E7CFE0D4D3E278CE304E60BB0267B599050EB)

.png?sfvrsn=752edba_0&MaxWidth=1000&MaxHeight=600&ScaleUp=false&Quality=High&Method=ResizeFitToAreaArguments&Signature=0F6E7CFE0D4D3E278CE304E60BB0267B599050EB)

Disruptions and the Future of Health Insurance

In dentistry, the largest single payer of dental treatment is private insurance. Direct payments from these insurance carriers make up 50% of all payments made to private practice dental offices, according to 2020 Health Policy Institute data. Therefore, it is important to fully understand the market forces and potential changes to the health insurance model.

Large-scale changes from fee-for-service to VBC require an infrastructural and philosophical change for organizations. Hospitals are more frequently investing in and transitioning to a future of VBC; however, many are struggling with the scaling and implementation of such novel approaches.19 This paradigm shift requires providers to move toward a population-health, data-driven and team-based approach to patient care. VBC systems are just one example of potential changes to the fee-for-service payer model of oral healthcare.

The explosion of tools available for advancing the use of automation, digital platforms and other low-cost scalable technologies have the ability to influence dental insurance reforms and create solutions to problems that were difficult to solve in the past. Advances in AI with image detection and natural language processing20,21 can automate and streamline insurance processes that have historically been inequitable, slow and costly. Access to data through AI utilization is an important component to unlocking a more complete understanding of the dental market. Insurance carriers receive and collect a large amount of clinical data linked with payment information. While these data are rarely shared, dental schools have a dental data repository (bigmouth.uth.edu),22 and larger national dental insurance companies are now profiting from systems using their data.

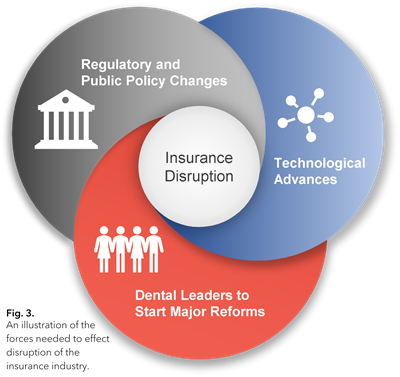

Additionally, large-scale changes in dental insurance would not be possible without regulatory or public policy changes (see Fig. 3). Public support for regulatory reforms to health insurance has become an ever-popular and growing subject of debate. Patients and providers are collectively seeking changes to the current model of third-party payment for healthcare services.

Additionally, large-scale changes in dental insurance would not be possible without regulatory or public policy changes (see Fig. 3). Public support for regulatory reforms to health insurance has become an ever-popular and growing subject of debate. Patients and providers are collectively seeking changes to the current model of third-party payment for healthcare services. Given the current climate of technology and public policy, there is potential for major changes to the current dental insurance reimbursement model. High-functioning committees within dental organizations like AGD have the potential to effect these changes and strategically influence and negotiate new terms. We implore you to be a future leader to effect meaningful change toward a more equitable and patient-centric reimbursement system in dentistry.

Aaron Glick, DDS, FAGD, is adjunct clinical associate professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Dentistry and fellow at Texas Medical Center Innovation, both in Houston. Ashley Tello, DDS, is in private practice in Granbury, Texas. Jessica Glick, DO, is a family medicine physician at Memorial Hermann Medical Group in The Woodlands, Texas. To comment on this article, email impact@agd.org.

References

1. Thomasson, Melissa A. “From Sickness to Health: The Twentieth-Century Development of US Health Insurance.” Explorations in Economic History, vol. 39, no. 3, 2002, pp. 233-253.

2. Morrisey, Michael A. Health Insurance. 3rd ed., Health Administration Press, 2020.

3. Eisen, Roland, and David L. Eckles. Insurance Economics. Springer Berlin, 2011.

4. Himmelstein, David U., et al. “Medical Bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: Results of a National Study.” The American Journal of Medicine, vol. 122, no. 8, 2009, pp. 741-746.

5. Calcoen, Piet, and Wynand P.M.M. van de Ven. “How Can Dental Insurance Be Optimized?” The European Journal of Health Economics, vol. 19, no. 4, 2018, pp. 483-487.

6. Blackwell, Debra L., et al. “Regional Variation in Private Dental Coverage and Care Among Dentate Adults Aged 18–64 in the United States, 2014–2017.” NCHS Data Brief, no. 336, 2019, pp. 1-8.

7. Vujicic, Marko. “Time to Rethink Dental ‘Insurance.’” The Journal of the American Dental Association, vol. 147, no. 11, 2016, pp. 907-910.

8. Perrault, Evan K., et al. “Preventive/Office Visit Patient Knowledge and Their Insurance Information Gathering Perceptions.” The American Journal of Managed Care, vol. 25, no. 12, 2019, pp. 588-593.

9. Song, Jihee, et al. “The Impact of the Affordable Care Act on Dental Care: An Integrative Literature Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 18, no. 15, 2021, p. 7865.

10. Bui, Fiona Q., et al. “Association Between Periodontal Pathogens and Systemic Disease.” Biomedical Journal, vol. 42, no. 1, 2019, pp. 27-35.

11. Long, Michelle, et al. “Trends in Employer-Sponsored Insurance Offer and Coverage Rates, 1999-2014.” Kaiser Family Foundation, 21 March 2016, kff.org/privateinsurance/issue-brief/trends-in-employer-sponsored-insurance-offer-and-coverage-rates-1999-2014/.

12. Zhang, Angela, et al. “The Impact of Price Transparency on Consumers and Providers: A Scoping Review.” Health Policy, vol. 124, no. 8, 2020, pp. 819-825.

13. “The State of Claims: Survey 2022.” Experian Health, 2022, experian.com/content/dam/noindex/na/us/healthcare/state-of-claims-2022.pdf.

14. “The Change Healthcare 2022 Revenue Cycle Denials Index.” Change Healthcare, 2022.

15. Grimm, Christi A. “Some Medicare Advantage Organization Denials of Prior Authorization Requests Raise Concerns About Beneficiary Access to Medically Necessary Care.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General, April 2022, oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-09-18-00260.pdf.

16. Miranda, Geraldo Elias, et al. “Administrative and Clinical Denials by a Large Dental Insurance Provider.” Brazilian Oral Research, vol. 29, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1-8.

17. Schneider, Eric C., et al. Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly: Health Care in the U.S. Compared to Other High-Income Countries. The Commonwealth Fund, 2021.

18. Jivraj, Ashiana, et al. “Value-Based Oral Health Care: Implementation Lessons from Four Case Studies.” Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice, vol. 22, no. 1S, 2022, p. 101662.

19. Abou-Atme, Zahy, et al. “Investing in the New Era of Value-Based Care.” McKinsey & Company, 16 Dec. 2022, mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/investing-in-the-new-era-of-value-based-care.

20. Chang, Jennifer, et al. “Application of Deep Machine Learning for the Radiographic Diagnosis of Periodontitis.” Clinical Oral Investigations, vol. 26, no. 11, 2022, pp. 6629-6637.

21. Glick, Aaron, et al. “Impact of Explainable Artificial Intelligence Assistance on Clinical Decision-Making of Novice Dental Clinicians.” JAMIA Open, vol. 5, no. 2, 2022, p. ooac031.

22. Walji, Muhammad F., et al. “BigMouth: Development and Maintenance of a Successful Dental Data Repository.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, vol. 29, no. 4, 2022, pp. 701-706.