The Evidence Behind Electric Toothbrushing: What’s New out There?

This article is sponsored by Crest Oral-B.

When we are practicing dentistry, we often say: “It works in my hands,” or “I believe in this material,” or “This is how I have been doing it for years.” And usually we feel that the product or procedure really does work in our hands. However, even when we feel that something works in our hands or truly believe in a specific product or treatment modality, we must remember that our perceptions are not always necessarily correct. We must collect and analyze data in a way that is comprehensive and unbiased.

Bias is not a trait we exhibit on purpose. We all want to make things better for our patients and select the best treatments for them, but sometimes when we are working for a long time, we may, even unconsciously, prefer specific treatments that we perceive to be more successful. Our minds can sometimes trick us into seeing fewer failures or complications with treatments we think are better.

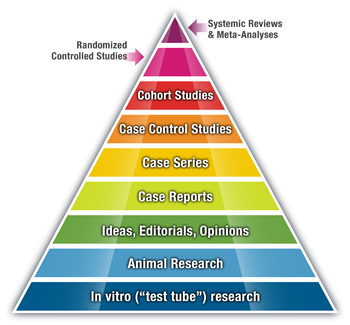

Discussions about evidence-based practice often refer to a pyramid of different levels of evidence (Fig. 1). This pyramid is built on a base of in vitro laboratory research and rises through evidence levels of increasing quality until it reaches the top of the pyramid, which is formed by systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The idea behind the pyramid is that all of these levels of evidence are needed to develop or support a product or treatment, but, as the study categories move up in the pyramid, they provide stronger evidence related to bringing the product or treatment chairside.

evidence (Fig. 1). This pyramid is built on a base of in vitro laboratory research and rises through evidence levels of increasing quality until it reaches the top of the pyramid, which is formed by systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The idea behind the pyramid is that all of these levels of evidence are needed to develop or support a product or treatment, but, as the study categories move up in the pyramid, they provide stronger evidence related to bringing the product or treatment chairside.

Fig. 1: The Pyramid of Evidence

In systematic reviews and meta-analyses, we evaluate or analyze data from a variety of randomized controlled trials or studies on a specific topic. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses compile outcomes in a way that gathers the maximum available information from the current literature on the specific topic.

A recent example is a systematic review that a colleague and I published in the April 2020 issue of The Journal of the American Dental Association.1 In this study, we evaluated randomized controlled trials comparing oscillating-rotating toothbrushes with sonic toothbrushes. The findings showed that there is some evidence to suggest that oscillating-rotating toothbrushes might remove more plaque and reduce the number of bleeding sites better than other powered toothbrushes.

A recent example is a systematic review that a colleague and I published in the April 2020 issue of The Journal of the American Dental Association.1 In this study, we evaluated randomized controlled trials comparing oscillating-rotating toothbrushes with sonic toothbrushes. The findings showed that there is some evidence to suggest that oscillating-rotating toothbrushes might remove more plaque and reduce the number of bleeding sites better than other powered toothbrushes.

Fig. 2:The Oral-B iO new

oscillating rotating electric

toothbrush.

A recent sponsored supplement of the International Dental Journal provided three randomized controlled trials evaluating the new iO toothbrush. In one study designed to compare the new iO to a manual toothbrush during an eight-week time period, Grender et al found that the odds ratio for transitioning from being a gingivitis patient to a healthy patient after only eight weeks was 14.5 for iO users.2 In other words, there is a 14.5 times higher chance that

patients will cross the disease threshold and become healthy if they use the iO instead of a manual toothbrush. That is a significant, clinically relevant difference.

In another randomized controlled study, Adam et al compared the new iO to a sonic toothbrush during an eight-week time period.3 In that study, the odds ratio for transitioning from being a gingivitis patient to a healthy patient after eight weeks was 4.75. Thus, there is a 4.75 times higher chance that patients will cross the disease threshold to become healthy patients if they use the iO instead of a sonic toothbrush.

Furthermore, a systematic review and meta-analysis on all the data collected from the randomized controlled studies performed in Procter & Gamble was also recently published. This enabled analysis of a large total amount of patients and statistical units.4 This study showed that 65% of subjects transitioned to a ‘generally healthy’ gingival state with iO, while only 20% of manual brushers had the same success. Odds ratio calculations revealed that iO users were 7.4 times more likely to become healthy. The same trend was demonstrated when iO was compared to sonic toothbrushes — 65% of subjects transitioned from gingivitis to a healthy state when using iO versus 51% of subjects using sonic toothbrushes.

Of course, these results tie in well to our main goal as dental practitioners, which is to prevent oral diseases and promote oral health. Achieving this objective is the sometimes-overlooked key to success in our profession.

Liran Levin, DMD, FRCD(C), FIADT, FICD, is a professor of periodontology, University of Alberta, Canada.

References

1. Clark-Perry, Danielle, and Liran Levin. “Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Studies Comparing Oscillating-Rotating and Other Powered Toothbrushes.” The Journal of the American Dental Association, vol. 151, no. 4, 2020, pp. 265-275.

2. Grender, Julie, et al. “An 8-Week Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the Effect of a Novel Oscillating-Rotating Toothbrush versus a Manual Toothbrush on Plaque And Gingivitis.” International Dental Journal, vol. 70, suppl. 1, 2020, pp. S7-S15.

3. Adam, Ralf, et al. “Evaluation of an Oscillating-Rotating Toothbrush with Micro-vibrations versus a Sonic Toothbrush for the Reduction of Plaque and Gingivitis: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial.” International Dental Journal, vol. 70, suppl. 1, 2020, pp. S16-S21.

4. Grender, Julie, et al. “The Effects of Oscillating-Rotating Electric Toothbrushes on Plaque and Gingival Health: A Meta-analysis.” American Journal of Dentistry, vol. 33, no. 1, 2020, pp. 3-11.