The Physical Toll of Dentistry

Dentists are dedicated to their patients’ oral health. But are they putting their bodies at risk in the process?

Bethany Valachi, PT, DPT, MS, CEAS, recalled when her husband faced the toughest decision of his dentistry career: sell his dental practice or learn to live with severe lower back pain. He was 35 years old.

As a doctor of physical therapy, Valachi thought she could relieve his pain with the traditional therapies she used with her patients. But his relief was only temporary, and the pain returned after a few days of working in the operatory.

Valachi realized the answer was in her husband’s physical working environment, so she became a certified ergonomic assessment specialist to address things from a different angle. Ergonomics adjusts a job to a worker — not the other way around — to get to the root of the problem.1

“It wasn’t until after implementing the proper ergonomics in the operatory that his pain permanently resolved,” Valachi said. “Now, 27 years later, he is still practicing dentistry full time without back pain.”

Valachi discovered that her husband’s experience was quite common. She authored “Practice Dentistry Pain-Free: Evidence-Based Strategies to Prevent Pain & Extend Your Career,” and established Posturedontics to provide online continuing education (CE) video training courses to educate clinicians on how to resolve work-related pain.

Dentistry lends itself to the development of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) due to the awkward postures, repetitive motions and poorly designed tools used to deliver care. Although MSDs are the most researched type of workplace health problem in dentistry,2 many dental clinicians struggle with pain and aren’t getting the help they need.

“The problem of work-related pain is so pervasive in the industry that many dental professionals simply don’t believe it is possible to work without pain,” Valachi said.

Fortunately, advancements like ergonomically designed equipment and professional workplace assessments are reducing dentistry’s toll on the body, but making adjustments before pain begins remains a challenge for dental clinicians.

The Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorders in Dentistry

Musculoskeletal disorders in dentistry have been widely evaluated. Research suggests that the prevalence of MSDs in dentistry ranges between 64%–93% among dentists, dental hygienists and dental students.3

One study compared MSD pain among physicians, surgeons and dentists and found that dentists had the highest rates. Of the respondents, 61% of dentists had MSD pain, compared to 37% of surgeons and 20% of physicians.4 Similarly, a 2018 literature review citing a study of Swedish dentists showed “dentists are at the higher end of the spectrum of healthcare professionals in terms of severity of musculoskeletal injury and lost work time.” An additional study found that 15% of dentists studied left clinical work or cut their hours as a direct result of MSD pain.2

Alan Hedge, PhD, CPE, C.ErgHF, professor emeritus in the human-centered design department at Cornell University, echoed the research showing that dental work carries MSD risks.

“By their mid-40s, many dental clinicians have significant problems, and it leads them to retire a lot faster than they may want to,” Hedge said.

These “significant problems” may present differently depending on the clinical role. One study found that dentists report a higher prevalence of back and neck pain (36.3%–60.1% and 19.8%–85%, respectively), while dental hygienists struggle with more hand and wrist issues (60%–69.5%).3

Shoulder pain is also common, Valachi said, citing that “nearly 80% of dental professionals complain of neck and shoulder pain, and about 65% experience low back pain.” What about dentistry makes it uniquely susceptible to musculoskeletal pain? Taking a closer look at the everyday parts of dental clinical practice will shine light on the causes — and the solutions.

Why Dentistry Causes Pain

Causes of MSDs in dentistry can be divided into four categories:

- Posture.

- Repetitive movements.

- Tool design.

- Time demands.

Posture

Whether it’s to achieve the best view of the patient’s teeth or to ease the use of a particular tool, dental clinicians often assume postures unlike any other profession and hold them for extended periods of time, Valachi explained.

Whether it’s to achieve the best view of the patient’s teeth or to ease the use of a particular tool, dental clinicians often assume postures unlike any other profession and hold them for extended periods of time, Valachi explained.

“These prolonged, non-neutral postures lead to a damaging series of microtraumas in the body — muscle ischemia, trigger points, disc degeneration, muscle imbalances — that can culminate in an MSD,” Valachi said.

Keeping the spine neutral, or in a straight line, is a postural challenge for dentists. But, as Anshul Gupta et al. explained in the 2014 article, “Ergonomics in Dentistry,” repeatedly bending and twisting the back puts a huge strain on the spine’s intervertebral discs.5

“More stress is placed on the spinal disks when lifting, lowering or handling objects with the back bent or twisted compared with when the back is straight,” the authors wrote. “Manipulative or other tasks requiring repeated or sustained bending or twisting of the wrists, knees, hips or shoulders also imposed increased stresses on these joints. Activities requiring frequent or prolonged work over shoulder height can be particularly stressful.”5

Repetitive Movements

Dental procedures often require repetitive motions over a long period (e.g., scaling or filling), which can lead to fatigue and strain on the overworked muscle(s). If the repetitive motion requires additional force, or if you’re in an awkward position, the risk for pain or injury increases.5

Tool Design

Dental tool design has historically strained the hands, leading to carpal tunnel syndrome and other hand MSDs. Like the spine, the hands can experience strain when in a non-neutral posture (when the hand and wrist are not in line). Small, smooth tools that require a pinch grip as well as vibrating tools can all lead to MSDs in the hand and arms, Hedge explained.

“Dental clinicians often have to use their hands in awkward positions by pinch-gripping tools that may be vibrating and aren’t really well designed, and they do this throughout the day,” Hedge said. “We know that the risk of hand-related musculoskeletal injury increases when the posture of the hand is out of alignment.”

Hedge also said force plays a role, as more force puts stress on the soft tissues in the hands and arms.

“The smaller the tool in terms of its diameter, the more force it takes,” Hedge explained.

Time Demands

Romelo Rodriguez, CPT, MAT, RTS, HLC, is a Toronto-based personal trainer with Lateral Health Network who quickly recognized how the time demands of dentistry contributed to MSDs.

“Dental clinicians have one of the toughest professions when it comes to trying to find a proper ergonomic position when treating their patients,” Rodriguez said. “When you add a lengthy workload on top of that, it seems inevitable that many of the common chronic problems arise.”

The body’s ability to recover from work is important to its ability to sustain over time. According to Gupta et al., using the same muscles for long periods of time leads to fatigue, and “... the longer the period of continuous work, the longer the recovery or rest time required.”5

General dentists preach prevention to their patients, but are they taking the same approach to their musculoskeletal pain?

Awkward postures, poorly designed tools and heavy workloads are not dentistry requirements. Fortunately, advanced ergonomic techniques can help dentists avoid the practices that accelerate wear and tear on their bodies.

Preventing Musculoskeletal Disorders

Preventive approaches can ease dentistry’s burden on the body, but experts say that clinicians tend to wait until they’re in pain to address it.

“The biggest problem I find with dental clinicians seeking help is that most only seem to seek help after the issues have become problematic, as opposed to making ergonomic adjustments and implementing effective exercise schedules and routines early on as preventive measures,” Rodriguez said.

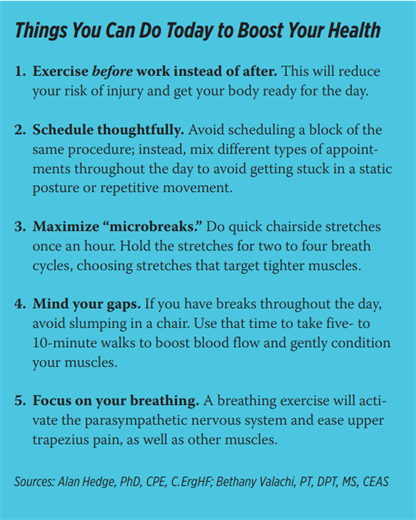

When it comes to prevention, Rodriguez emphasized the need for clinicians to commit to doing the right exercises regularly to keep their bodies healthy throughout their dental careers. The focus is less on exercise intensity and more on consistency, he said.

“Having clinicians stay consistent with one or two workouts a week with me, along with a prescribed four to six exercises and stretches to do daily on their own outside of our workouts, has had great results in stabilizing, strengthening and mobilizing the common problem areas,” Rodriguez said. “I put an extra emphasis on exercises to strengthen all of the rotator cuff muscles, the abdominals, the posterior deltoids and the muscles that support a strong thoracic [mid-back] spine.”

Like Rodriguez, Katrina Klein, RDH, focuses on “posture enhancement fitness” when helping her dental clients prevent MSDs. Klein not only owns Sacramento-based ErgoFitLife, which specializes in helping dentists prevent and treat MSDs, but she’s also a dental hygienist, certified personal trainer and certified ergonomics assessment specialist. “

Weight training, maintaining 30 minutes of cardio at least three times a week, daily foam rolling, stretching and weekly yoga are things we dental athletes need to do to stay pain-free or reduce existing pain,” Klein said.

In addition to establishing healthy exercise and stretching habits, Klein’s work in ergonomics helps clinicians implement healthier changes in the office environment to reduce the risk of MSDs. Klein performs ergonomic assessments with dental professionals as they perform treatments on patients, coaching them on operator setup, operator positioning, patient positioning and ergonomic strategies.

A key component of the ergonomic office is maximizing the ergonomic design of tools and equipment. The profession has come a long way toward designing better tools and devices to make dentistry healthier.

“Ergonomics has changed the form of many objects to put less strain on the hand by reducing grip force, reducing vibration to the hand, and keeping the hand and wrist in neutral postures,” Hedge said.

If you’re not ready to invest in an ergonomic tool, Hedge said wrapping a narrow, circular tool in padding or tape to increase its diameter may make it more comfortable to use and lessen the pinch force needed.

Loupes and saddle stools are two other equipment considerations. Valachi advises dentists to purchase truly ergonomic loupes.

“Most of the loupes on the market today are non-ergonomic and force the dental professional into an unsafe forward head posture, which can lead to neck pain,” Valachi said. “This is gradually improving, as new prism loupes were recently introduced.”

For stools, Valachi avoids the one-size-fits-all approach.

“Selecting the wrong stool or adjusting it incorrectly can lead to disc herniation, spondylosis, spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis,” Valachi said. “It all starts with evaluating your lumbar curvature and selecting a stool accordingly.”

Hedge offers a word of caution when using ergonomically designed products: A well-designed tool alone won’t alleviate stress or prevent injury. And it’s a smart strategy to first assess why you need the tool before buying it.

“Often, people think, ‘I’ll go and buy something,’ but they don’t use it properly,” Hedge said. “Figure out what you need and why you need it before you buy something. Just because something says it’s ergonomic doesn’t mean it’s appropriate for you.”

If you’re not ready to invest in a professional ergonomic assessment, one way you can determine your ergonomic needs is to consider the position of your hands and body when you’re doing tasks. To help with the visualization, Hedge recommends having someone take a video of you to help illuminate areas of poor posture. “When are you bending your head too much or twisting your neck? How can you reposition yourself and the patient so you don’t use poor posture?

When are your hands in an awkward position? Do you need a different stool or active sitting chair that allows you to move while performing a task? Look at how you’re working, and see what needs to change,” Hedge said.

Another way to prevent pain is through patient positioning in the exam chair. Valachi explains that with proper positioning, the clinician can comfortably deliver 70% of their treatment from the most ergonomic clock position: 11–12 o’clock. This involves proper adjustment of headrests, positioning of the patient and use of positioning aids.

“The dentist’s posture can be dramatically improved by angling the double-articulating headrest steeply downward when working on the upper arch, then asking patients to scoot up until they are comfortable,” Valachi said. “This will place the edge of the headrest at the patient’s nuchal line, thereby supporting the cervical curve and greatly improving the patient’s tolerance to being reclined.”

Strategic scheduling is another effective preventive tool, Hedge said. Booking varying procedures requires different tools and postures, which limits the opportunities for holding yourself in static postures for too long.

“Scheduling four hours of fillings is a recipe for disaster,” Hedge said. “Mixing appointment types will reduce the amount of force and effort, which reduces the risk of injury.”

There is some good news when it comes to preventing MSDs: They generally don’t pop up overnight, so you have time to put things back on a healthy trajectory when you address them early on.

“MSDs are slow developing, progressive and cumulative,” Hedge said. “You get warning signs — and, if you pay attention, you can prevent them.”

The first sign is discomfort, Hedge said, like an achy hand at the end of the day or first thing in the morning.

“This is the body’s way of telling you to stop doing what you’re doing,” Hedge said. “Don’t ignore it. If you stop and change what you’re doing, then the injury will not progress.”

Unfortunately, when an MSD isn’t corrected, it can affect the way you work or even prevent your ability to practice dentistry entirely. Reduced range of motion, weak grip strength, nerve-related pain in the arms and hands (e.g., tingling, numbness and burning), and muscle pain and fatigue are all-too-common experiences for many dental clinicians.5

Practicing in Pain: Treatments to Ease Musculoskeletal Disorders

If pain is preventing you from working, you need to take a break, Hedge said.

“If you have a back or wrist injury or a neck strain, continuing to work will exacerbate the injury, and, eventually, it will be debilitating,” Hedge said. “The body will repair most injuries with time, but it won’t repair if it is not rested.”

Hedge explains that there’s no quick fix with overuse injuries. You can’t speed up muscle healing. Although certain therapies like ice, heat and pain medication will ease your recovery, rest will ensure that you heal fully. And surgery, he said, should be a last resort.

Once you’ve given your body rest, seeing a physical therapist or other exercise professional can help you understand why the injury happened and how to prevent it from happening again.

“Far too often, clinicians will not understand the nuances of their specific problem and will jump to assuming that they should be doing specific things to address a specific issue,” Rodriguez said. “For example, if I am experiencing lower back pain and I decide that I need to start running a few times a week or jump into a yoga class right away to cure it, this will often not resolve the issue and could worsen it.”

Exercise as a treatment should focus on performing exercises that correct muscle imbalances, Valachi adds. And, in some cases, this means avoiding certain exercises that are generally helpful for most people.

“Due to the postural demands of their work, dental clinicians are prone to developing muscle imbalances unlike any other profession,” Valachi said. “Generic exercise routines often include several exercises that can exacerbate these imbalances and worsen pain. One example is the vertical row, which strengthens the upper trapezius. While not a problem for the general population, this can send dental professionals into a vicious pain cycle.”

Ergonomics and Dentistry: Is the Industry Doing Enough?

Despite advances in dental ergonomics, work-related health problems remain a major issue in dentistry. Research shows that dentists generally aren’t taking advantage of professional ergonomist consultations and assessments to reduce their MSD risk.2

A possible explanation for why dentists haven’t adopted ergonomics in their clinical practice is a lack of education and awareness from the industry. That starts with dental schools, Hedge said, which haven’t incorporated the importance of proper posture and ergonomics into the curriculum. Continuing education programming on ergonomics in dentistry is also lacking, he said.

“Dental schools and the profession need to increase the amount of ergonomics education,” Hedge said. “The latest and greatest ergonomic guidelines, techniques and tools are constantly being developed, and they should be presented at annual conferences. Dentists need to stay abreast on how to work in a safe way.”

Looking at the dental workforce as a whole and projecting into the future, the issue of workplace safety needs to be a higher priority for the industry, Hedge said.

“In the United States, we are seeing a shortfall in dentists, and we can’t afford to be injuring people,” Hedge continued. “The profession has to help its professionals by improving the well-being of dental workers.”

Although MSDs are physical in nature, they can erode mental and emotional health when ignored. What starts as a sore back or stiff hand can be the first sign of a disorder that can unravel a promising dental career and diminish your quality of life.

“When we are in pain, we can become irritable with our spouses, friends, staff and patients,” Klein said. “We slow down and become less productive. We feel pressure from the lack of financial success and can experience burnout, substance abuse, depression and anxiety. Our body is our most important asset to achieving good mental health and a full and rewarding lifestyle.”

Kelly Rehan is a freelance journalist based in Omaha, Nebraska. To comment on this article, email impact@agd.org.

References

1. “Ergonomics - Overview.” Occupational Safety and Health Administration, United States Department of Labor, osha.gov/ergonomics. Accessed 11 June 2022.

2. Moodley, Rajeshree, et al. “The Prevalence of Occupational Health-Related Problems in Dentistry: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Occupational Health, vol. 60, no. 2, 2018, pp. 111-125.

3. Hayes, Melanie J., et al. “A Systematic Review of Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Dental Professionals.” International Journal of Dental Hygiene, vol. 7, no. 3, 2009, pp. 159-165.

4. Rambabu, Tanikonda, and K. Suneetha. “Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Physicians, Surgeons and Dentists: A Comparative Study.” Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research, vol. 4, no. 4, 2014, pp. 578-582.

5. Gupta, Anshul, et al. “Ergonomics in Dentistry.” International Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry, vol. 7, no. 1, 2014, pp. 30-34.