Whole-Body Dentistry: How Nutrition Affects Oral Health

Dentists can play a pivotal role in improving patients’ dietary health. But is nutritional counseling really within a dentist’s scope of practice?

At her practice in Elk Grove, California, Sireesha Penumetcha, DDS, MAGD, LLSR, FICOI, sees a family whose members are pictures of health. The mother is a nutritionist. The kids are homeschooled, so they don’t have access to soda and candy in cafeteria vending machines. The family follows a vegan diet and had a sparkling oral health history with no caries or decalcification.

But a strange thing happened.

During a recent preventive exam, Penumetcha discovered that the previously caries-free children all had tooth decay.

The family practiced good oral health hygiene and had a nutritious diet, so Penumetcha wondered what changed. She discovered it wasn’t what the family ate but rather how they ate that created problems.

“They juiced their vegetables and fruits,” Penumetcha said. “Even though the food is healthy, the form in which they ate it produced a strong combination of fruit acids and sugars.”

Penumetcha could have simply treated the symptom. But, by digging a bit deeper, she identified the real issue and educated her patients about how to prevent it.

“The old concept of dentistry is to restore and repair teeth and gums,” Penumetcha said. “But now, we need to focus on education, prevention and maintenance more than just drilling and filling teeth. The first step toward any treatment should be finding the underlying root cause, which is nutrition and habits.”

Discussing nutrition with patients may feel like you’re blurring the lines between dentistry and dietetics, but it could provide a clear pathway toward integrating dentistry as a crucial component of whole-body healthcare.

For Penumetcha, nutrition is an important aspect of oral and systemic health. She doesn’t shy away from dietary conversations, as they help her achieve her practice goal of addressing “the complete foundation of health” for her patients.

“We have always educated and advised our patients regarding the effects of soda, acids on teeth — including fruit acids — and not brushing following snacking,” she said. “Overall health begins with oral health. Thus, proper nutrition and habits are equally important for oral health.”

How does the general dentist who has no nutrition background have these conversations with patients? A comprehensive refresher in key oral health and nutrition concepts is a good place to start.

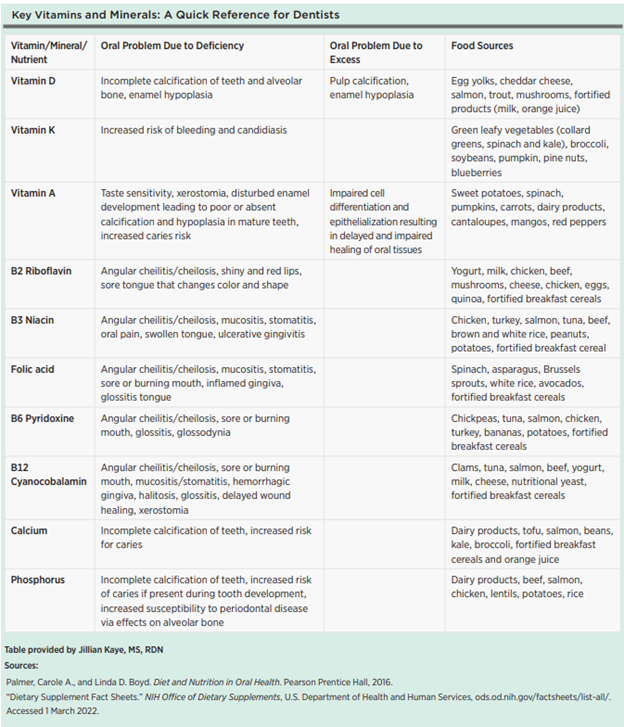

The Oral Healthcare Effects of Vitamins and Minerals

Jillian Kaye, MS, RDN, adjunct clinical instructor/registered dietitian nutritionist at the New York University College of Dentistry, helps dental students build a base of nutritional expertise before they start practicing.

More than just knowing the effects of vitamins and minerals, Kaye said dentists knowing the food sources of these nutrients is crucial. (See “Key Vitamins and Minerals.”)

“If you are talking with a patient about their vitamin K intake, and they ask what foods contain vitamin K, will you know?” Kaye said. Vitamins A, B and D, along with calcium and phosphorus, all have major oral health implications, although Kaye explained that vitamin A deficiencies are rare in the United States and other developed countries.

Vitamin B (B2, B3, B6 and B12) deficiencies are most common in older adults, alcohol users, people with restricted diets (e.g., veganism or vegetarianism), and people with gastrointestinal issues or recent surgeries. Because the B vitamins are often all in the same foods, it’s common to be deficient in all of them.1

Enamel hypoplasia is an oral health condition linked to vitamin D deficiency and excess. Older adults, people with restricted diets (e.g., veganism) and those living in places with limited sunlight have increased risk for vitamin D deficiency.1

Vitamin D supports the functions of calcium and phosphorus in remineralizing and strengthening teeth. Vitamin D stimulates calcium and phosphorus absorption in the intestines and kidneys. The bones mobilize calcium to level out the blood calcium, but that can lead to increased risk for osteoporosis (in adults) or rickets (in kids), Kaye said. Vitamin D deficiency will typically result in low-to-normal calcium and phosphorus in the blood, but deficiencies aren’t the only problem with vitamin D.

“Depending on where you live, you may get enough vitamin D from the sun,” Kaye said. “I always recommend vitamin D levels be checked before taking a supplement, as too much vitamin D leads to overcalcification of the teeth.”

Nutrient deficiencies are something that John Nosti, DMD, FAGD, FACE, FICOI, based in Mays Landing, New Jersey, said he wished more dentists discussed with patients. He explained that several nutritional deficiencies have ties to oral conditions, such as angular cheilitis/cheilosis, stomatitis, glossitis, oral ulcers and burning mouth syndrome.

“When these conditions present themselves, I feel it is important to question the patient on their dietary intake, including the possibility of vitamin deficiencies, lack of adequate water intake on a daily basis (chronic dehydration), as well as alcohol consumption,” he said. “It is surprising how often patients are lacking in vitamins A, B, C and D; have extremely low water intake on a daily basis; and consume several alcoholic beverages per day.”

Regarding macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins and fats), a major point Kaye aims to teach dental students is how fermentable carbohydrates are linked to caries — and how they can then explain this to future patients.

Simply put: Any carbohydrate is fermentable, but high-fermentable carbs (e.g., sucrose, or table sugar) are more cariogenic than low-fermentable carbs (e.g., lactose, the sugar in milk).

“Everyone has an idea of sugar and caries, but regular carbs can have that same effect,” Kaye said.

Kaye doesn’t advocate for eliminating carbohydrates from the diet; instead, they are best paired with proteins and fats. Unlike carbohydrates, which digest in the mouth, proteins and fats digest later in the digestive system, so they’re less cariogenic, Kaye said.

“Protein and fat also tend to reduce the adherence of carbohydrates to the teeth, which helps with clearance from the mouth and inhibits bacterial growth,” Kaye said. “Dentists can help patients understand how to make better choices by providing recommendations that pair carbs with proteins and fats.”

Like proteins and fat, nonnutritive sweeteners (e.g., aspartame) are cariostatic, so dentists may recommend them as a compromise for sweet-toothed patients.2 However, Kaye recommends caution when advocating for these sweeteners.

“The [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] generally regards them as safe, but there’s really not much long-term research on how they affect us,” Kaye said.

There’s a lot more to the nutrition and oral health story than “sugar is bad.” Dentists should know the importance of vitamins and minerals to whole-mouth health and understand that all carbohydrates have varying levels of cariogenic effects.

It’s Not What You Eat, It’s How

Amr Moursi, DDS, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Pediatric Dentistry at the New York University College of Dentistry, said the sugar-focused conversations dentists often have with patients are missing a key element.

“The misconception is that it’s all those cookies or jellybeans causing cavities, but it’s the frequency of exposure to any carb,” Moursi said. “The bacteria in your mouth that cause cavities don’t care if the carb comes from candy or grapes.”

Moursi explained that constantly snacking throughout the day — even on healthful foods like dairy, whole grains and fruit — provides a steady diet for oral bacteria. The message should be on limiting carb-centric snacking.

“You can brush five times a day, and it will still be tough to compete with that constant bathing of your mouth in carbs,” Moursi said.

How you eat plays as big, if not bigger, a role in your oral health than what you eat. Penumetcha’s family of vegan patients are a prime example of how eating a nutrient-rich diet the wrong way can produce dental problems.

Penumetcha explained that when her patients stopped juicing, their oral health improved. Like Moursi, Penumetcha agreed that dietary behaviors are worth exploring with patients rather than asking them to solely curb their sugar consumption.

“There are other aspects I wish got more attention than sugar, such as the habit of snacking throughout the day, juicing, the six-meal concept diet, intermittent fasting and other fad diets,” she said.

Dentists can present several simple solutions to change dietary behaviors that decrease caries and erosion risk, including having structured and brief mealtimes throughout the day (limit snacking and grazing) and using straws with sweetened or acidic beverages. After meals, rinsing with water, chewing sugar-free gum, and brushing and flossing help — but wait 20 minutes before brushing if the food or beverage was acidic.2

Dietary Associations With Oral and Systemic Disease

How diet leads to caries is well known, but nutrition also plays several roles in the management and prevention of periodontal disease.

Diet-dominated conditions, such as obesity, heart disease and uncontrolled diabetes, increase periodontal disease risk. Poor nutrition also inhibits the immune system from functioning properly, which affects wound healing. Nutrient deficiencies, namely vitamins C and D, and calcium, have links to periodontal disease risk, too.2

Dehydration is another nutritional aspect that can have a significant impact on a patient’s oral health, Nosti said, noting that dehydration may lead to caries and even difficulty in achieving adequate anesthesia in the dental practice.

“Patients who are dehydrated often feel some soft-tissue signs of anesthesia, but at inadequate levels for performing operative or surgical procedures,” Nosti said.

On the topic of hydration, one of the problems Nosti has seen is patients being confused by marketing and labels that deem products “healthy.” He cites flavored sparkling water beverages as an example of a product that, while it combats dehydration, may introduce a different oral health problem.

“Flavored sparkling beverages are commonly viewed as a healthy alternative to soda for hydration due to their lack of sugar,” Nosti said. “But LaCroix can have a pH as low as 2.7, which, if consumed often, can cause acid erosion of the dentition.”

Nosti reported a similar issue with his caries patients. “In years past, it was common for patients to blame high sugar-content foods or drinks as the culprit for their caries rates,” Nosti said. “However, processed foods, chips and crackers, which can be marketed as ‘healthy,’ are just as easily causing increased levels of caries, and most patients aren’t aware of this.” Another example of patients who are ready to discuss nutrition are those being treated for a sleep-related breathing disorder, or obstructive sleep apnea, Nosti said.

“While oral appliances and CPAPs [continuous positive airway pressure machines] are effective in treating these disorders, many patients would improve their symptoms greatly by losing weight,” Nosti said. “I have found that simply opening the conversation with these patients regarding what their physician feels is a cause of their sleep-related breathing disorder is helpful. When they respond that they should lose weight, I ask them if they would like assistance.”

Nutrition and digestion start in the mouth, and it’s the gateway to the rest of the body. Dentists are among the first-line clinicians to recognize when a patient may have nutritional deficiencies, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea or a sleep-related breathing disorder, Nosti explained.

Nosti pointed to the well-established association between heart disease and periodontal disease, as well as links connecting obesity, heart disease and obstructive sleep apnea, as evidence for dentists to incorporate nutritional counseling as part of a whole-body approach to dental care.

“It is unequivocally necessary for dentists to be able to discuss these things with patients,” Nosti said. “We are accustomed to discussing nutrition for avoidance of caries, but this should be extended into these other areas.”

Exploring the Gut-Oral Microbiome Link

Among the emerging areas of interest in nutritional and oral health is the connection between oral health and digestive health — more specifically, how the gut microbiome is linked to the oral microbiome.

Saliva helps with the first step of chemical digestion (salivary amylase) and moves food out of the mouth and through the digestive tract, Kaye said. Saliva is mostly water, but it contains minerals like calcium phosphate that are essential for healthy teeth.

“Chewing sugar-free gum helps increase salivary flow, which can increase pH levels in the mouth and help with remineralization,” Kaye said. “Protein, zinc and vitamin A deficiencies have been correlated with decreased salivary flow.”

Healthy saliva starts the chemical digestive process, so the link between the mouth and the gastrointestinal tract isn’t surprising. Anything that enters the gut first existed in the mouth, after all. But now researchers are offering clearer insight into the oral-gut microbiome axis, or how an unhealthy gut leads to an unhealthy mouth (and vice versa).

Periodontal disease is one condition heavily implicated in the oral-gut axis. One of the first reactions after the onset of gum disease is bacteria from the oral microbiome traveling to the gut, triggering inflammatory responses elsewhere in the body. The gut microbiome plays a major role in supporting the immune system. Without a fully functioning immune system, the mouth becomes susceptible to other forms of oral pathogens.3

When digestive health is compromised, the imbalance in the gut microbiome leads to whole-body inflammation, which can manifest as oral health problems.

In many cases, a dentist is the first clinician to detect signs of digestive diseases (e.g., irritable bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease). Oral signs like a swollen tongue, candida infections, inflamed gums (not plaque related) and mouth ulcers are often the first clues of a problem in the gut.3,4

Balanced nutrition leads to a balanced microbiome throughout the body. This, in turn, allows the immune system to function optimally. Kaye also explained that it’s not just the mouth and gut bacteria that “talk” to each other, but that imbalances in the gut microbiome also communicate with your brain, impacting a person’s hunger/ satiety response. This may lead to more eating, meaning more exposure to cariogenic foods and, thus, more caries risk.

How to Talk to Patients About Proper Nutrition

Before approaching a nutrition conversation with a patient, Kaye recommended banishing two concepts.

First, there’s no such thing as an optimal diet (“Nothing works for everyone,” Kaye said). Second, remove your own dietary preferences and beliefs from the conversation.

“You have an individual in your chair with a vast medical history,” Kaye said. “You can’t make an off-the-cuff recommendation because that could have huge implications on their oral and overall health.”

With an objective and customizable approach in mind, the next step to adding a nutritional counseling component to your practice is creating a patient intake form, Nosti said. He suggested including fields that allow patients to decide how and when to discuss nutrition and weight, which helps remove shame from the conversation.

Nosti recommended simple, nonconfrontational questions on the questionnaire, such as these examples from the American Council on Exercise:

- Would you like your health professional to discuss your weight with you?

- What words are you comfortable with when referring to your weight?

“I have also found simply asking questions such as, ‘Can you share with me what nutritional supplements you are taking?’ or ‘Do you take a high-quality multivitamin daily?’ to be easy entryways to the nutritional discussion,” Nosti said. “Another idea is to use an opening statement, such as, ‘I feel that your daily nutrition could be playing a role in the things that I am seeing in your oral health. Based on this, can you share with me information regarding your daily nutritional intake?’”

Weight and obesity are often an inherent part of the dietary conversation, and these sensitive issues can put patients off. It’s crucial to set up the context between oral health and overall health before launching into a dietary conversation, said Moursi, who said he’s had success with this approach when speaking with parents of pediatric patients.

“A good way to talk about it is to begin by asking, ‘I’d like to measure your child’s BMI [body mass index] because that’s important not only for overall health but also oral health. Have you talked to anyone about that? I can put you in touch with someone who can help,’” Moursi said. “It’s not an easy conversation, but I’ve found that parents have been receptive to it.”

Online nutrition courses and local nutrition professionals who understand the connection between oral and systemic health provide additional resources to boost a dental practice’s dietary counseling offerings. (See “Online Resources” to learn more at right.)

Online nutrition courses and local nutrition professionals who understand the connection between oral and systemic health provide additional resources to boost a dental practice’s dietary counseling offerings. (See “Online Resources” to learn more at right.)

Despite the evidence showing the strong bond between oral health and nutrition, some dentists may be hesitant to incorporate dietary counseling into their practices. Moursi encouraged skeptical dentists to reflect on the prevention-driven direction of dentistry, along with the fact that the average adult sees their general dentist more than their personal physician. It’s an opportunity to play a pivotal clinical role in an increasingly integrated healthcare environment.

“There’s probably no more important part of a prevention program for oral health than nutrition,” Moursi said. “It has just as much significance and impact as talking about brushing and fluoride toothpaste. It really is that critical.”

Kelly Rehan is a freelance journalist based in Omaha, Nebraska. To comment on this article, email impact@agd.org.

REFERENCES

1. Pflipsen, Matthew, and Yevgeniy Zenchenko. “Nutrition for Oral Health and Oral Manifestations of Poor Nutrition and Unhealthy Habits.” General Dentistry, vol. 65, no. 6, 2017, pp. 36–43.

2. Marshall, Teresa A. “Nutritional Assessment and Oral Health.” Decisions in Dentistry, 1 Aug. 2016, decisionsindentistry.com/article/nutritional-assessment-and-oral-health/. Accessed 1 March 2022.

3. McHill, Carrie. “Gut Health: A Key Link Between Oral and Systemic Wellness.” RDH Magazine, 22 July 2021, rdhmag.com/patient-care/article/14204716/gut-health-a-key-link-between-oral-and-systemic-wellness. Accessed 1 March 2022.

4. “How Your Gut Microbiome Links to a Healthy Mouth.” Dr Steven Lin, 24 July 2018, drstevenlin.com/how-your-gut-microbiome-link-to-a-healthy-mouth/. Accessed 1 March 2022