The Risk of Prescribing Antibiotics with No Documentation

Various states and provinces have different regulations governing the documentation of medications dispensed in the dental office. Controlled substances, in particular, require careful record-keeping. Does this level of attention need to be paid for antibiotic prescriptions? The following case illustrates the pitfalls that can occur when antibiotics phoned into a pharmacy after hours or during the weekend can cause problems for a dentist who does not keep careful records of these prescriptions.

A 34-year-old male patient was treated by the subject dentist for several years and, over the course of treatment, had several root canal procedures, crowns and implants placed.

Four years into treatment, a problem developed with tooth No. 4, and a new post was placed temporarily to retain the crown until the tooth could be extracted and temporized. That evening, the patient called the subject dentist complaining of pain, and an antibiotic (Amoxicillin, 40 pills) was phoned in to a pharmacy but not documented in the dental records.

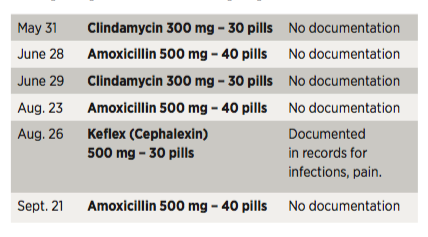

Over the next several months, the patient presented with continual pain associated with tooth No. 4, along with other problems, and called or texted the dentist over several weekends. The pattern continued, and antibiotics were telephoned into the pharmacy. This pattern, where the patient refused treatment and the dentist continued to prescribe antibiotics, resulted in the following antibiotics being phoned in (the number of pills prescribed are also noted):

Except for one exception, these prescriptions were not documented in the dentist’s records. The subject dentist explained that his protocol was to have the patient come in early the following week to be seen; at that time, the prescription would be documented. However, this protocol was not followed in the five instances noted. At least three times, another antibiotic (Clindamycin or Cephalexin) was substituted for the first one prescribed and, according to the subject dentist, the patient was told to discontinue the first one. However, the patient admitted in his deposition that these instructions were not followed.

The subject dentist claimed that recommendations were made for the infected tooth to be extracted and for other definitive procedures such as root canal therapy to be performed to deal with other active infections resulting in pain. The patient refused, however, for various reasons.

The last appointment with the subject dentist was on Sept. 18, and on Sept. 26, the patient presented to the emergency room with complaints of fever and abdominal pain. These symptoms had never been described to the subject dentist and, although the patient showed improvement after being given Flagyl and Cipro, he was admitted to the hospital on Oct. 16 with a diagnosis of Clostridium difficile (C. diff). He was transferred to another hospital where his medical insurance would cover him and then was discharged about one week later.

The patient had no further contact with the subject dentist but retained a lawyer and sent a notice of intent to file a malpractice lawsuit one year after the admission. The lawyer had pharmacy records and pointed out the failure of the five prescriptions noted in this article to be documented in the dental records. There were two main allegations: the dentist’s failure to document the antibiotics prescribed and prescribing multiple antibiotics on a continual basis over a four-month period with no definitive treatment of the source of the infections.

Initially, the claim was deemed to be defensible; malpractice was denied, and the patient’s lawyer was notified of this position. After several months, a summons and complaint were served to the dentist. The discovery process commenced and depositions were taken. As evidence was gathered and potential liability was considered, there were major concerns about the lack of definitive treatment that the dentist knew should have been done in lieu of the antibiotic prescriptions, as well as the lack of record-keeping. The dentist also sent the patient some self-incriminating text messages that were worrisome.

Almost two years after the claim file had been opened, there was an opportunity to mediate the case in an effort to settle prior to the expensive task of designating experts. A mediation session was successful in reaching settlement, which stipulated that the claim be dismissed by the court and that a release be signed in exchange for a payment being made to the patient and his lawyers. The settlement amount was far less than the patient wanted but was substantial due to the severity of the C. diff symptoms and long-term effects.